Super grass

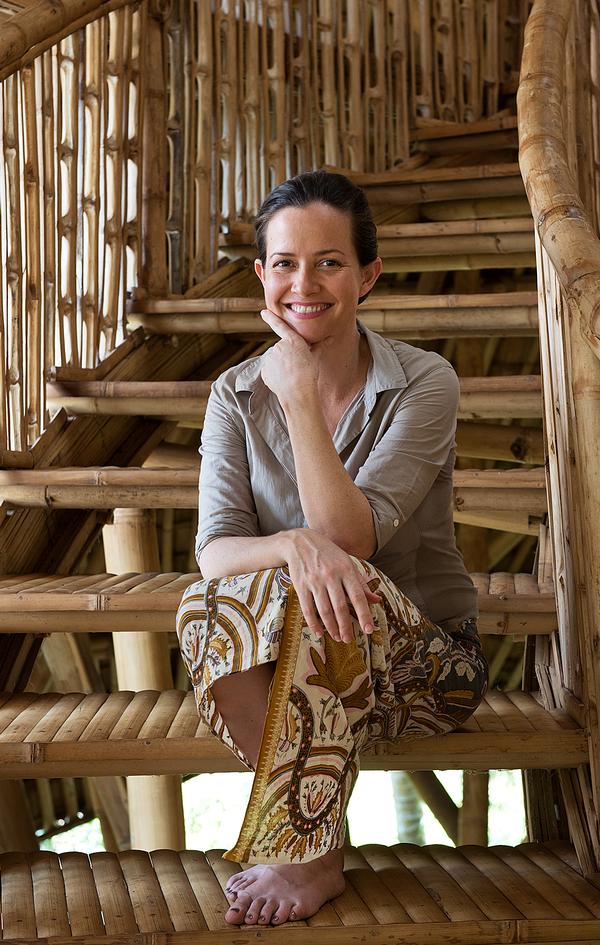

Ibuku

A Bali-based design firm, has been attracting attention for its sustainable, elegant bamboo buildings. Now its sights are set on the resort market and colder climates, too. Its founder, Elora Hardy and lead architect, Ewe-Jin Low share their vision

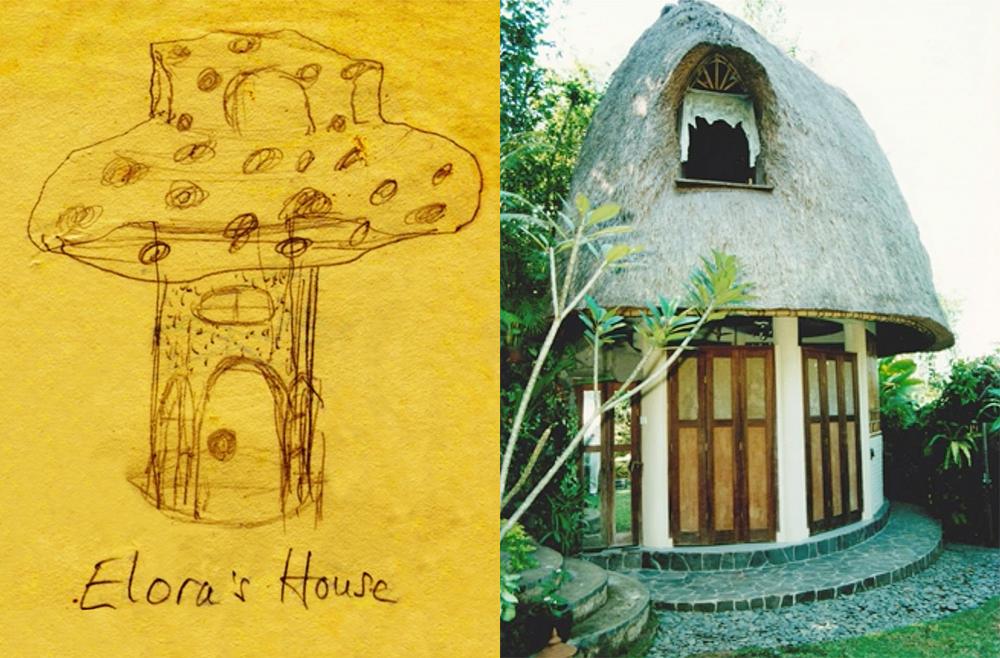

When Elora Hardy was a little girl growing up in Bali, her mother asked her to draw a picture of her dream home. She drew a fairy mushroom house. But rather than simply putting the drawing on the wall, her mother went a step further: she built it.

Twenty-five years later, that same creative boldness – the drive to turn seemingly fanciful ideas into reality – is central to Hardy’s own vision, as founder and creative director of Ibuku: a Bali-based company that designs and builds soaring, curving, beautiful, solid and sustainable structures almost exclusively from bamboo.

Hardy founded Ibuku in 2010, but the seeds for the firm were sown much earlier. Raised in Bali until she was 14, Hardy moved to the US in 1994, going on to earn a fine arts degree from Tufts University before forging a career as a textile print designer for Donna Karan in New York. Meanwhile, back home in Bali, a groundbreaking building project was getting underway.

Although the island already had a long tradition of building temporary structures with bamboo, the arrival of young Western designers in the 1970s took the discipline to a new level. One of these designers was Linda Garland, a friend of Elora’s father, the jewellery designer John Hardy.

The sustainable and functional credentials of bamboo as a building material were clear. It grows from a shoot to a structural column in three to four years, compared to 10 or 20 years for soft woods, and absorbs far more carbon dioxide. Bamboo clumps regenerate annually if selectively cut. And despite being extremely light, the material has the compressive force of concrete and the strength-to-weight ratio of steel.

The challenges were bamboo’s vulnerability to insects and the weather. But the development of new treatment methods – such as soaking the poles in boron solution (a type of salt solution) to keep bugs at bay – combined with innovative building techniques to minimise the impact of rain removed those obstacles.

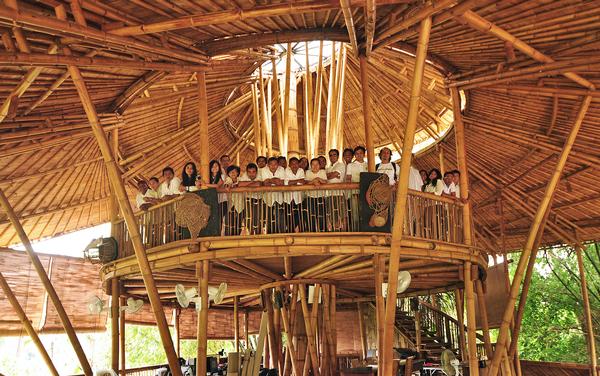

THE GREEN SCHOOL

In 2007, inspired by Garland’s work, John and his wife Cynthia (Elora’s stepmother) gathered a dream team of builders, artists and local craftsmen to create Green School: a campus comprised entirely of open-sided, sustainable bamboo buildings, which together with a similarly avant-garde curriculum, would help children, “to cultivate physical sensibilities that will enable them to adapt and be capable in the world… to develop spiritual awareness and emotional intuition, and to encourage them to be in awe of life’s possibilities.” (Green School philosophy).

Back home for a visit, Hardy was blown away by what she saw. But what’s more, it coincided with a time when she was searching for a career path that more closely reflected her values. “I needed to be part of something sustainable. It really came down to that,” she explains. “It became obvious that what was happening in Bali was really well-aligned with what I cared about.”

By the time the school was complete, the two lynchpins of the design team, a German builder called Joerg Stamm and Aldo Landwehr, a Swiss artist, were no longer involved: Stamm had only ever committed to a consulting role and Landwehr had passed away. “There was a bit of a swirl of ‘What do we do?’,” says Hardy. “Because the guys who had been working with them had this amazing skillset and had developed several really key structural concepts for how to work with the material.”

The answer to that question was Ibuku, which roughly translates as “Mother Earth”. Over the past five years, the firm has built close to 70 permanent bamboo structures on Bali, including 15 new classrooms at Green School; an exclusive community of luxurious private homes called Green Village; and an expansion of Bambu Indah, a boutique resort property owned by John and Cynthia Hardy.

While Elora Hardy has brought both entrepreneurial spirit and creative vision to the table, she is clear that the firm’s story both precedes and exceeds her personal contribution. While the media is quick to focus on her own story – the little girl from Bali who forged a high-flying career in New York then left it all behind to build bamboo houses – she would far rather talk about the collaborative work of her 130 full-time staff, including the 30-strong design team.

Since Hardy told her fairy mushroom house story at a TED talk early in 2015, interest in Ibuku has grown dramatically. With a strategic move into the resort market and overseas expansion on the horizon, the firm is on the brink of a whole new phase. In the following interviews, Hardy and lead architect, Ewe-Jin Low, explain how they’re using bamboo to reinvent the rules of building design and what sustainable architecture really means.

Elora Hardy,

Creative Director,

Ibuku

Why is bamboo so appealing as a primary material?

Whenever we’ve looked at integrating other materials over the years the question has been: “How does it even begin to compare sustainably?” When my father was planning Green School he really understood that there isn’t anything else that goes from nothing to timber in four years, with just rainwater, and also regenerates. Other trees take many more years to grow and have to be replanted. Recycled timber is a possibility but it doesn’t give us anything for the future, because it will run out. If you have access to recycled timber and want to use it for your house, great. But if you’re building a campus for kids to look at and think about? You want something that they can build the next thing they imagine out of, because it will still be available.

What was so pioneering about the building methods developed at Green School?

The buildings at Green School took their cues from the material. It’s as if they said: “OK, here’s a pole, a structural column: it’s curving, it’s tapering, it’s irregular, it’s extremely strong, it’s very long. What shall we do with it?” So it was really about using that natural form.

My brother Orin [now head of Ibuku’s landscaping division] was working with Joerg [Stamm] at Green School when they came up with the idea of bundling splits of bamboo to achieve structural curves in the building. To me, it’s showing such respect for the material: to let it guide you, instead of saying: “We want to build a house and this is what we want it to look like. How do we get the material to do that for us?” In our best uses of it, the bamboo really gets to show off and serves us well. But we also have to protect it, which is why we have big overhanging roofs on so many of our structures. And I love that. Yes, it’s strong, it’s versatile, but it needs to be protected. And that’s true for people, too.

How would you sum up Ibuku’s philosophy?

Our aim has really been to push the boundaries of this one material and create spaces that people can relate to, that are comfortable and luxurious, and more importantly, that inspire a sense of wonder. I think the reason people feel connected to the buildings is that they feel connected to the natural world by being in the buildings, even though they’re manmade. And that sense of connection and creative inspiration allows us to redesign the future for the world – because bamboo is a material that really sets up a good future.

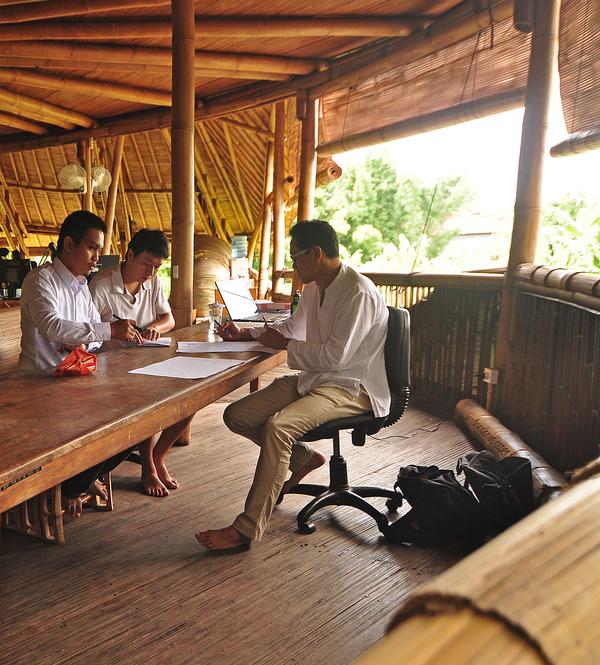

One unique aspect of your design process is that your team works primarily from scale bamboo models rather than architectural drawings. Why is that?

Well, initially we couldn’t find bamboo craftsmen able to read architectural plans! So it was about working directly with the craftsmen and creating something they could relate to. But what happened then was that designing in three dimensions with the stick models really influenced the kind of shapes we came up with. I could sit with the team and work on sketches all day, but I couldn’t picture it until we’d worked on the model. And working on the models really affected what we built in a way that was quite intuitive.

Now it’s a much more sophisticated process. We use a lot of drawings as well as models in order to communicate all the details, because our architects don’t sit with the craftsmen all day every day on site any more. But designing in 3D like that is pretty cool.

What’s the biggest challenge of working with bamboo?

Most of our bamboo homes have a few air-conditioned rooms. If it’s just a holiday home, some clients request not to have it as they want a real jungle experience, but I feel pretty strongly about having at least one space in a house in the tropics where you can dry out and keep your photos and books. So enclosing for air-conditioning is the most challenging part – because we even use curved members for our window frames. If we just backed off and became more conventional in how we build, the problem would go away, but we’re still in that phase of really wanting to push the envelope.

What makes some projects more challenging than others?

Some projects just go really smoothly while others feel like they’re stuttering. Sometimes the team says we started building on the wrong day according to the Balinese calendar. I haven’t figured it out, but we do make a point now of offering the right offerings on the right day, at the foundation stage… You’ve got to pay the proper respects; you can’t underestimate the power of that.

Your first foray into the resort market has been at Bambu Indah on Bali. How did that come about?

The original buildings at Bambu Indah are Javanese bridal houses, which Javanese families were quite eager to sell off as they became more able to afford new and modern structures. So my dad started collecting them and the resort of Bambu Indah was made from his collection.

The centrepiece and one the earliest bamboo structures at the resort was the Minang House, which is a replica of a traditional Minangkabau clan house. And they’d also built a very simple, long barn, which functioned as a restaurant. Last year, we added a really beautiful, tented structure with a tower in the middle at the far end of the barn, and it became the kitchen. So it’s a little inverse, because typically the kitchen is hidden in the back of the development and the restaurant is glorified, but in our case the restaurant is very simple and the kitchen is glorified.Another structure we've built at Bambu Indah is a guest room called the Sumba House. It's a replica of a traditional Sumbanese house, which has a very distinctive tall, pointed roof.

How much potential do you see to expand outside of Bali?

We've had an overwhelming number of enquiries since the TED talk. The major response has been: Can you come and build this here? And by here, I mean Toronto, Holland... and of course India, Malaysia and Australia, too. Some of those places will require major efforts in the mundane world of building code and approval processes for them to even consider anything bamboo-related, so we'll have to see.

There are many parts of the tropical world that would be the intuitive next step for us, but big picture: bamboo should be used in cold climates as well. Combined with appropriate insulative materials, there's no reason you can't have a towering bamboo structure in Denmark with a very smartly insulated roof - whether that's with rammed earth or something else - but using bamboo as the structural core. Ultimately we would build with bamboo anywhere except a desert, and even then it's just a matter of drying it out properly.

What drives you?

In Bali there's so much development, and people often say, "How do you feel about that?" And I'm like, "Can we please not talk about it?" because there's nothing constructive I can do except to show an alternative. It's such a world of compromise, people say: "We need to use the cheapest available option, and maybe we can do it a little less badly and slightly more sustainably." It's too late for that. We need to really stretch our creative, innovative minds - which humans are extremely good at. We've shown throughout history the changes we can make in decades, and that's speeding up more and more. And I want to be part of that world of possibility and positive change.

From an emotional standpoint, what I feed off is the feeling that I get, and the feeling I see in other people, when they walk into buildings we've made - there's just this little bit of delight and this little bit of wonder. It's something very deep and very simple and I find it very rewarding.

Ewe-Jin Low,

Lead Architect,

Ibuku

Why did you become an architect and how has your career progressed?

It was really just an early desire to create, and finding I had an ability to sketch and draw things: as simple as that. I trained at Brighton University in the UK and got my first job with a small architecture firm in Sussex, working on industrial business parks. After having a child, my wife and I decided to go home to Malaysia, where I spent a couple of years with a premier firm working on hotels before setting up my own practice. Eventually, I moved my family to Melbourne for my children to go to school. After several years there working for other people, I went back to Malaysia to work for a friend on projects in Pakistan and Dubai. But after a couple of years, I’d had enough and came back to Melbourne to set up my own practice, focusing mainly on church, social and housing projects. I still run it with the help of friends.

How did you come to Ibuku?

I saw an advertisement online for a senior architect, and it interested me because I grew up with bamboo when I was a kid. So I decided to apply for it even though I wasn’t looking for a job at the time. It was a long process – I had five or six interviews – but eventually they chose me.

What does your role involve, and how much of an adjustment has it been?

I manage a team of about 30 people, covering architecture, graphics, interior design and furniture, as well as a new landscaping and permaculture branch.

As an architect without much bamboo experience coming into this unique world, it has taken time to blend in. Initially, everything was foreign to me. The only advantage I had was the language: the Malay and Indonesian languages are pretty similar, so I could understand 60-70 per cent. But design methods and building methods I’ve had to learn the hard way.

Nine months down the line I can now get more involved in the design process, but my job is not to initiate design; that’s Elora’s role. My role is to assess the design, to look at how to streamline things, to look at areas I think can be improved or made equal to what we do in the other world – the world other than bamboo. I have a good general background in architecture, and a lot of experience of running projects from start to finish, so what I have learned I apply. That has really helped me start shaping this office from what it is to what it’s going to be.

As an architect, how does working with bamboo compare to working with other materials?

I had to unlearn a lot of things then learn them again. Bamboo is not uniform like a piece of milled timber or a piece of steel. With bamboo buildings it is very difficult to get the levels and dimensions to exactly what is wanted, because bamboo flexes: the more weight there is on the building, the more it shifts and changes. On a traditional building of timber, steel or concrete, you will never run out by a few millimetres. Bamboo can run out drastically if it’s not controlled. So the challenge is choosing the right bamboo, making sure the on-site team is sharp at keeping within the dimensional set-ups and adjusting where necessary.

Detailing is another example. You can do a detail as nice as you want by imagining and sketching it. But when you get on site and talk to the bamboo artisans, it can change because they come up with something even better, or the situation changes. One of the main things Elora told me when I joined Ibuku was: “You have to be flexible like the bamboo.”

What’s your biggest challenge right now?

How to make the openings in our buildings more modular. In the developed world, we take for granted when we specify a door or a window that we will get the opening built and our product will more or less fit into that opening. But bamboo is never straight, so that in itself is a challenge: how do you fit a door into an opening you’ve drawn as 1m by 2m, but which in the end is not square? So far we’ve done it by working with the skilled artisans here to purpose-build objects [such as glass panels] that fit into that irregular space. We can afford to do that on our bespoke projects. But for more commercial projects we’re now looking at creating a transitional surround to even out the curves and nodes around the opening so we can insert a standard door or window into it – possibly using laminate bamboo panels.

What’s next for the practice?

As Elora mentioned, we’re getting a lot of resort enquiries, both locally and from overseas. So the next step is probably a fully fledged resort, where we do the masterplanning as well as all the buildings. One of the first projects is likely to be a cliff-top resort here in Bali, which is currently in concept design. The big challenge there is how do you stop horizontal rain and wind from coming into the building and still get a view? And also how do you use bamboo to excite a discerning user who is used to five- or six-star experiences?

We’re also looking at another two resorts on nearby Indonesian islands, and potentially two or three more overseas. These will be seaside resorts in tropical or sub-tropical locations where the climate is similar to Bali, and also one in a cooler climate.

What particular challenges does working overseas present?

Firstly, the buildings in colder climates will have to be closed in. A lot of our buildings are curved and organic in shape, so we may have to go more square or modular or componentised to solve that problem. We're looking at how glazing systems will work, and how to achieve a floor and a roof that are insulated using materials that are sustainable.

There's also the challenge of transporting traditional Balinese artisans overseas. We had a [restaurant] job in Hong Kong recently and we had some cultural issues. Balinese workers are spiritual: they need to go to temple, they need to do their offerings, and in Hong Kong that was hard!

"The next step is probably a fully fledged resort, where we do the masterplanning as well as all the buildings"