Attractions

Biomuseo

A year on from the opening of Frank Gehry’s long-awaited museum of biodiversity in Panama, Kath Hudson speaks to the team who made it happen

It was in the works for 15 years and had its fair share of delays, but in October 2014 the Frank Gehry-designed Biomuseo finally opened in Panama City. It’s a statement piece of architecture from Gehry, whose wife is Panamanian; a riot of bold, colourful metal canopies rising from the Amador Causeway, at the mouth of the Panama Canal.

Aiming to recreate the Bilbao effect, Panamanian leaders began talking to Gehry in the late 90s about designing a museum for the causeway site. The Amador Foundation was formed in 2001, and initial public funding was secured; in 2002 Gehry signed on to the project, with an initial budget of $60m (the final cost was $100m, with a further $15m required for the final three galleries).

Since then, construction has been a stop/start process, with various setbacks, including challenges with funding, the issues surrounding three changes of government and other construction challenges. “The path to completing the project was very challenging and took a long time,” says project architect Anand Devarajan. “The process and procedures of constructing a project in Panama was very different from that we would expect in other locales.”

Despite the setbacks, the project still embodies the original ideals for the museum, says Devarajan. The museum celebrates the region’s rich, natural biodiversity in both the architecture and the content. Focusing on the importance of the isthmus and its biodiversity, its scientific content was researched and curated by teams from the Smithsonian Institute and the University of Panama, and the striking exhibitions and galleries were created by Bruce Mau Design.

It features eight galleries, with 4,000sq m of exhibition space, areas designed for temporary exhibitions, a shop, café, public atrium and botanical garden. The foundation is still fundraising for a further three galleries, which will include a large aquarium.

KEY FIGURES

Project conceived: 1999

Ground broken: 2005

Museum opened: October 2014

Initial budget: $60m

Final cost: $100m

Funding still required: $15m

Visitors so far: 120,000

Resident admission: $12

Non-resident admission: $22

Number of galleries: Eight

(five already built, three stlll to be built)

Age of the isthmus of Panama: 3m

Size of Panama: 75,000sq m

Size of museum: 4,000sq m

Size of museum gardens: 24,000sq m

Anand Devarajan,

Partner,

Gehry Partners, LLP

What appealed to Gehry Partners about this project?

Frank Gehry had a strong tie to Panama through his wife Berta and was intrigued by the various landscapes and cultures within the region. When the client communicated to us the intent of building a museum for Panamanians to highlight the biodiversity of the region and advocate for its conservation, the museum’s mission became very interesting to our office. Additionally, the site they had chosen in Amador, overlooking the Panama Canal and Panama City, was incredible.

Where did the inspiration come from for the architecture?

The expression for the architecture emerged as a synthesis of multiple things, including the storylines of the museum’s narrative, a response to the amazing site location and understanding existing built structures in the region.

How does the architecture relate to both Panama and the museum content?

The colours became a distinctive element that evoked a connection to the vibrant imagery we saw in Panama City on the buses and industrial structures, the built landscape of Colon and the local textiles of the indigenous Indians.

The roof shapes work on a similar principle to the naturally ventilated structures built locally – albeit with a geometry that is far more expressive. The volumes and roofs of the museum allow views of the dramatic surroundings, including the islands beyond Amador, the Bay of Panama and the canal entry, high-rises in Panama City and the bridge of the Americas. The use of corrugated metal roofing, plaster walls, and concrete for the building’s exterior were chosen to relate to local building materials we saw used in Panama City.

We wanted to express the museum’s narrative in the design. Each gallery and programme element took on an architectural identity on the exterior, responding to the internal exhibits, as well as space programme requirements.

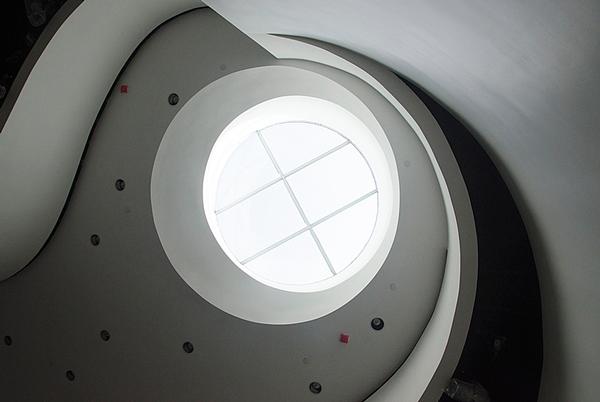

We saw the park and the museum’s setting as its own exhibition element, with connections to the narratives of the galleries inside. We wanted to blur the interior/exterior distinction. That required us to organise the building to create opportunities for visitors to reconnect to their surroundings and ways for landscape elements to engage the central atrium.

What were the biggest challenges of this project?

The path to completing the project was very challenging and took a long time. The process of constructing a project in Panama was very different than what we would expect in other locales. The unique geometry and quality control procedures required a steep learning curve from the team building the project.

Which aspect of the project are you most proud of?

One of the key design elements was the atrium. We imagined it as an exhilarating open-air civic space for Panamanians and are pleased about the way the space turned out.

The way that the exhibition elements knit together with the architecture has been fascinating to see, and it’s very pleasing to hear responses from the museum staff about school groups getting excited and engaged in the concept of biodiversity.

Can you describe the design process? How did you ensure the building fitted into its surroundings?

Since Frank had been visiting Panama with his family for many years prior to engaging on the project, he had a good amount of knowledge of the area. The rest of the design team learned about Panama during the process.

As with all of our projects, the design process is highly iterative, we tested out hundreds of design schemes, while honing a unique response for this particular project.

During the design process, Gehry Partners and Bruce Mau’s team had a great group of collaborators, including the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and local executive architect Patrick Dillon, who knew the region very well and participated in the design decisions.

Does this building incorporate any experiments which had not been used anywhere previously?

Most of the elements used in the museum are not new to our work or to the region. The unique thing about this project is the way we were able to combine all of the elements to create a new and interesting outcome.

"Since Frank had been visiting Panama for many years with his family, he had a good knowledge of the area"

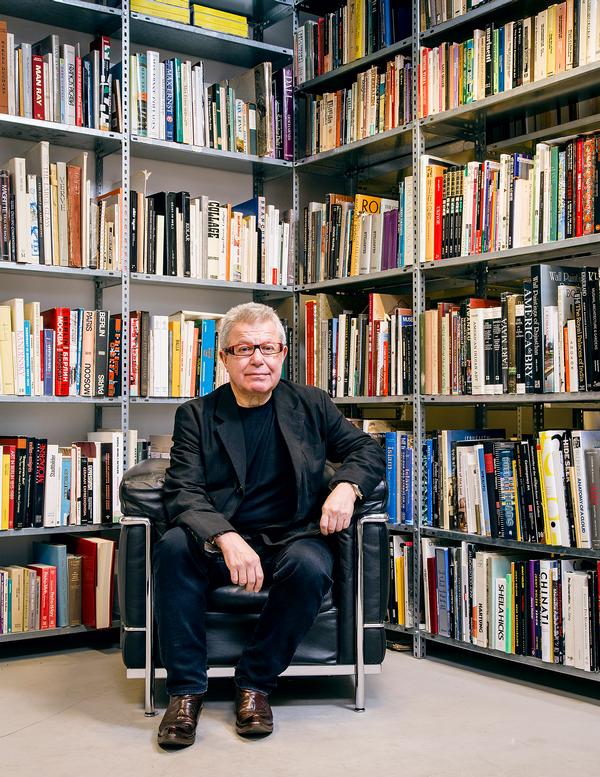

Bruce Mau,

Exhibition Designer,

Bruce Mau Design

How did you get involved with the project?

I had worked closely with Frank Gehry on several projects. Frank’s wife is Panamanian and one day she handed me a dossier and said: “You have to go to Panama.”

Why did the project appeal to you?

Firstly, to work with Frank is always an absolute dream. It’s also a spectacular site, at the entrance to the Panama Canal, with the backdrop of the city. It couldn’t get more impressive. And biodiversity is the most important subject we could address at this moment: it’s the future of life.

The boldness of this project was another big draw for me: the investment it represents for Panama is the equivalent of the US building 63 Getty Centers, all at once.

How did the design process develop?

We started from the inside out and Frank worked from the outside in. In essence, Panama itself is the museum and we are building the lobby. In some parts of the museum, the landscape you are looking at outside is the content.

There was a three part mandate: to educate, to change the way people understand things so they see the world differently, and to protect biodiversity. I didn’t want to lecture people, but engage and inspire them. Panama is full of wonderful stories, such as fish evolving differently in the two oceans and some bird species believing they still live on an island. Our job was to pull out those stories, and to create a wonderful experience that inspires people, makes them wonder and then satisfies that wonder. We’re not pushing stuff at people, we’re answering their questions.

How were each of the galleries given their own identity?

Firstly we asked what the key concepts were that we wanted people to walk away with, and then we broke them down into eight stories.

One of the galleries is called the Great Biotic Interchange. When Panama formed it connected two island ecologies, so two islands became one land mass and one ocean became two. Life from the north went south and life from the south went north. Some species flourished and others became extinct. That event is still taking place, with slow-moving things such as mosses, mushrooms and grasses still migrating.

In the gallery we create a stampede, so when people walk in they wonder what on earth is going on. Once we’ve created that state of wonder they’re ready to absorb information.

What is your favourite show piece?

Panamarama, which is a cinema cube. Visitors stand on a glass floor, so the cinema is below them and all around them. It takes them into the ocean, along the shore, to see the mangroves, then into the jungle, into the canopy and across Panama, to see the range of environments. People almost always applaud when they see it. The kids go crazy and adults sit on the floor, like kids.

What are you most proud of?

It’s an intersection of art, science and design. We had to make a declaration, it couldn’t be a modest building, it had to be something that people would see and they would want to know what it was. Frank really made that happen.

"Panama itself is the museum and we are building the lobby. In parts of the museum the landscape is the content"

Darien Montanez,

Curator,

Biomuseo

When was Biomuseo first mooted?

Back in 1998, Panama was going to receive a batch of land from the canal zone, so the government organised a series of workshops to determine how best to incorporate those lands into Panama City. We knew we wanted an architectural building, so a team of international designers was brought in, including Frank Gehry. He was invited to propose a series of projects along the Canal to be the cherry on top of the cake. As this was four years after the Guggenheim Bilbao opened, everyone in the world was aware of the power of an architectural masterpiece to bring new life to a city.

Unfortunately the project was shelved the following year when there was a change of government, but at that point the Amador Foundation was formed out of Panamanian and foreign business people, who still wanted to bring the project to fruition. They lobbied the new government and eventually convinced them to support it; they have also organised the funding.

What’s the relationship with the Smithsonian Institute?

The Smithsonian Institute has had a research base in Panama for 100 years and this has generated most of the content for the exhibits. We worked very closely with both the Smithsonian Institute and the University of Panama and have become the only Smithsonian-affiliated museum outside the US.

What story does Biomuseo tell?

The museum aims to bring the scientific knowledge generated in Panama to the general public. It tells the story of the isthmus of Panama: the different geological processes which made Panama rise out of the ocean. We see Panama as a bridge between two continents, but also as a barrier which split the tropical ocean in two.

We look at the consequences that event had locally, regionally and globally. We look at how Panama changed the world, such as redirecting the gulf stream, so Europe has milder winters than North America. Panama rising caused Africa to change from a continent of forests to one of savannahs. Some palaeontologists believe that this led to the formation of the human race, as primates had to come down from the trees and had to be more gregarious to survive.

How is the story presented?

Unlike most science museums, we didn’t have a collection of specimens. Instead, we decided the museum would be a collection of concepts.

Each gallery tells a story relating to Panama and its history. Instead of exhibit cases we have large murals, sculptures and interactive elements. On the downside, this approach meant that we had to start afresh with every gallery, because nothing is repeated.

What were the main challenges?

The main challenge is the complexity of constructing a building with North American quality control, but using Panamanian labour. The style in Panama is usually fast and cheap, so a lot of processes took longer because of the learning curve and these delays cost money.

What stage is the museum at now?

The first five galleries opened last October and we had more than 120,000 visits in the first year: 60 per cent of which were from Panama.

We’re still fundraising for the final three galleries, which are architectural spaces currently being used for temporary exhibitions. They will be the most expensive galleries, and will house an aquarium.

It is a very expensive project. Was it the right move to be so bold?

Thinking big and aiming high is what has made this museum successful. Having an architectural masterpiece makes it relevant to whole sections of the public who wouldn’t otherwise be interested in biodiversity.

The building acts as a bridge between the science world and the art world. It’s been difficult, but it’s undeniably worth it.

"The building is a bridge between the science world and the art world. Thinking big has made it successful"